8 Intercultural Practice as a Firefighter

Students in the Capstone unit ‘Intercultural Practice’ contributed these marvelous works based on their research projects in August to November 2021.

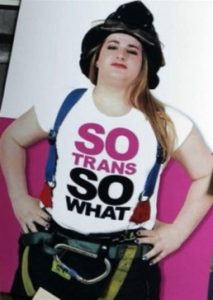

In this chapter, Carolyn shares her analysis of the Intercultural practices as a Firefighter at Adelaide Airport Fire Station.

Carolyn Denton

To what extent and in which ways can generative intercultural practice & interactions be developed on a Fire Station?

A fire station has a culture of its own, as well as sub-cultures. How can the Theory of Generative Interactions be put into practice to improve intercultural interactions and inclusion?

Introduction

This paper will discuss the potential opportunities for the practical application of intercultural interactions and communication protocols underpinned by generative theory in an airport fire station setting. Whilst this setting is not overtly intercultural, being a predominately white male Australian workplace, there is a female gender minority group (3 females out of approximately 50 employees). Gender diversity in emergency services has been highlighted as being critical to improved interactions and response to members of the public, as well as improved learning and skill development, culture, and teamwork (Young & Jones, 2018).

Gender is not the only cultural difference among the firefighters; there are also “sub-cultures” or rather, an assortment of cultural views, beliefs and opinions that are explored and shared in many conversations during “downtime”. There is also a cultural divide between Corporate and Frontline work groups of the company as well as between the Management team and Operational staff.

New, generative interactions across all sectors would be a positive step towards real inclusion and equity, rather than mandatory diversity training, which is undertaken with an “eye-roll” and a fear of disciplinary action. Generative interactions that foster respect, understanding, and inclusion would promote a self-full-filling causal cycle as the more frequent the interactions, the more willing people become to engage (Bernstein et.al. 2019). The impact of these actions would lead to improved professionalism and teamwork, meaning better efficiency and service quality for members of the public, airlines, local businesses and airport management. Furthermore, for the employees, they will feel more self-efficacy, leading to better engagement in taskings, reduce communication apprehension and self-isolation, and through these positive interactions build confidence and improve skills competencies (Cain, 2021).

“Diversity is being invited to the party. Inclusion is being asked to dance.”

Verna Myers

Work life as a female in the Aviation Rescue Firefighter Service (ARRFs)

Adelaide Airport Fire Station employs 50 staff, 47 of whom are male. It is located between taxiways on the airfield at Adelaide airport, West Beach, South Australia. The fire station is manned 24 hours a day, 365 days a year despite Adelaide airport having a 2300 curfew on passenger flights. The staff numbers are generally 10

during the day, plus the Station Manager from Monday to Friday, and 5 overnight. The Aviation Rescue Firefighting services in Australia are managed by Airservices Australia; a Federal Government agency who are also responsible for Air Traffic Control.

At Adelaide, there are 4 crews, A,B,C and D crew, with 2 teams on each crew. Currently, the 3 females are allocated to different crews, a decision reportedly based on sharing diversity and across the crews, but one that also helps from a practical standpoint, with limited space in the female facilities.

On a fire station, crews all share the station as a home away from home, sharing kitchen facilities, lounge-room area, study & admin areas, gym, showers, toilets, change-rooms, and dormitories. Adelaide airport fire station is very old and has had several “tack-on” upgrades over the years to accommodate increasing staff numbers and WHS issues. Currently there are separate ablution areas, however Airservices Australia are commencing project proposals for “Inclusive facilities”. The driving philosophy behind this project is to future proof the station facilities for potential LGBTQIA employees, but it will also impact current male and female staff. There is to be a prayer room and parent’s room (for breast-feeding) as well under the plan. Inclusion may imply that all genders are treated as though neutral however this does not acknowledge that having been raised by a gendered society, we have had different experiences, identities & norms, and as such have different expectations (Smith & Bamburger, 2021). This ideology is particularly relevant to the inclusive Facilities Project that is currently being undertaken by Airservices Australia. Forty out of the 40 people who responded to an inclusive facilities feedback survey were opposed to the project completely, based on a lack of consultation and lack of consideration regarding the practicality of such facilities in a fire station environment. This highlighted a cultural divide between the “office workers” who were trying to implement the project and the end users.

Daily duties at the station involve vehicle and equipment check and maintenance, training drills, physical training, physical training and responding to incidents a required. Incident response includes first aid calls, automatic fire alarms, fuel spills, hazardous materials, aircraft incidents, motor vehicle accidents and grass fires.

The way the roster runs means that teams overlap, providing more opportunity for diverse interactions than if they worked in isolation. During Adelaide’s COVID-19 lockdown period, social distancing requirements meant there had to be a new roster which did facilitate the isolation of crews to limit the scope of any potential viral outbreak to one crew. It was interesting how people had different views on this change. Some preferred it and felt their own crew grew closer and felt more like a team, whereas others missed the input and interactions with other crews.

The reason I have chosen this setting for a discussion about generative intercultural interactions is because it is a setting in which I operate regularly, and because I can ultimately put to practice the some of the generative practices and communication protocols to improve intercultural inclusion in my workplace. Recently I volunteered to be on the inclusive facilities team to provide insight and feedback to the project management team, and I am sure some of what I will learn through researching this discussion paper can be applied in that arena as well.

This working environment highlights the need for intercultural interactions not only for gender inclusion, but also at a corporate level. Communication protocols need to be improved from the top-down approach to a generative and collaborative approach that acknowledges the different communication discourses of corporate management and operational staff (Young & Jones, 2018).

Theory and Framework

Generative interactions need to be frequent, collaborative, inclusive, and promote cognitive adaptation to reduce prejudice based on stereotypes (Bernstein et.al. 2019; Crisp & Turner, 2011). Some staff may previously have had little opportunity to engage in intercultural interactions (Paluk, 2006), and although having more females in a traditionally male-dominated workplace provides opportunities for such interactions, merely increasing diversity numbers is not enough (Bernstein et.al. 2019). Introducing opportunities for generative interactions leads to new discoveries about culture and challenges previously held stereotypes (Bernstein et.al. 2019). Breaking down stereotypes and prejudice through repeated intercultural interactions reduces communication apprehension and self-segregation ( Bernstein et.al.2019).

Operational Communication Protocols dictate the terminology used on the station in terms of Telephone communications, use of the Public Address (P.A) system, Operational Response directions and Internal and External Radio Communications. Corporate Protocols outline acceptable communication standards for emails and publications. These are all formal communications and not ideal settings for any generative interactions. Furthermore, they are all recorded, and it can be said that this is a contributing factor to the heightened communication protocol awareness. Corporate Values guide communication behaviours as well, and Airservices Australia tout that they will “Work as One” – with Respect, Trust & Collaboration” (Airservices Australia, 2021). Protocols dictate that staff are addressed by Rank and Surname when using these formal processes, but of course when talking informally to one another, this does not occur and standard greetings are used, such as “Fellas, “Guys”, “Gentlemen” etc. I understand that this is just normal cultural discourse as is not meant to alienate the females on the station. Personally, I find that when men change what is their natural communication discourse, with an apology, or a correction or single me out when greeting or addressing the group, all it does it reinforce that I am “different” and that in fact, my presence is somewhat burdensome, to them because they feel like they cannot just be themselves. This gender specific direct communication – being spoken to as separate to the group – perpetuates oppression & exclusion and reinforces the stigmatism of having a female on station (O’Brien, 2020). Being different from the rest of a group already poses a barrier to acceptance without it being highlighted further (Craig & Jacobs, 1985). It can make me feel like an inconvenience that is putting them out. This aligns with a statement by Eriksen (2019) that women are often viewed as “special needs” staff.

Fire-fighting is historically a male dominated field, and still is, with only 2-6% of all firefighters in Australia identifying as female (SBS Australia, 2017). The profession has long been seen as a “boys club” but times are changing and although almost everyone supports women in the fire service, there will always be some opposition (Eriksen, 2019). As Wentling and Palma-Rivas (1999), cited in Bernstein et.al point out, diversity training can be seen as ineffective, and I believe that in my workplace it was probably undertaken from a politically correct standpoint and a fear of being accused of sexism. It also would have taken place several years ago and was more than likely heralded by a male who was internally rolling his eyes (given the well-known “boys club” culture of a fire station). Existing male staff feel that diversifying the workforce will threaten their workplace culture (Young, et.al.2018), and/or their position of power (Harris, 2019). This fear is exacerbated by stereotypes and lack of exposure to diverse intercultural interactions which can lead to communication apprehension, and “action paralysis” (Bernstein et.al. 2019; Young & Jones, 2018). It has been reported that men are generally less willing to engage in intercultural interactions than women (Yin & Rancer, 2003), so on a fire station, where 94% of the staff are men, this may propose a challenge. This apprehension can lead to self-segregation and the persistence of stereotypes (Bernstein et.al. 2019).

Now that females as firefighters are already more accepted, I do think a session on gender-inclusive language, such as outlined by the UN (2021) would be useful to stop these counter-intuitive “Politically Correct” faux-pas. This training should be undertaken by all staff, of all genders in an open forum (not individually online) to promote intercultural interactions & discussions and alleviate stereotypes (Bernstein et.al. 2019).

Strategy

At a station level, the current cultural communication competence of my own team leader is embarrassing. After some discussions, I have had male team members come up to me and tell me that they felt uncomfortable and embarrassed by the way the team leader addresses me. In trying NOT to single me out for tasks, he makes a point that he isn’t specifically addressing me, which does just that and segregates me within the discussion. Some of the longer-term staff like this man could benefit from more generative interactions which promote inclusive communications. The problem is that by nature of their role, they are not “part of the team” generally, making progress in that space problematic. Often people in supervisory roles self-isolate from the crew to maintain professional distance and thus miss out on intercultural interactions, and “diversity and inclusion specific” training programs are, I believe what has led to the inappropriate way in which my gender is needlessly mentioned, or phrases are said and then corrected to be “politically correct” just because I am present. I do empathize with the older males on the station, who awkwardly preface, re-phrase or apologise for their statements. They are trying to be politically correct, but that is not the same as being inclusive and often makes things worse by the excessive attention they give it (Mills, 2003). With the current management team being “Old School”, they can be resistant to change and hold firm to outdated, conservative norms (Craig & Jacobs, 1985). Fortunately, we have a group of younger, more liberal Sub-Station Officers who are advancing into those roles are enthusiastic about intercultural inclusiveness and many generative intercultural interactions already occur in the workplace. These generally occur in the mess, gym or stand-down room setting, during “down-time”. These interactions are organically occurring, social, and are frequent. Many discussions do revolve around hiring based on gender targets and whether or not there will be a compromise of service quality or employee quality standards (Mackintosh, 2018; SBS, 2017). Ideally, organizational strategies that aim to increase generative interactions should try to replicate this type of environment as staff are more likely to engage and this increases human capital which leads to improved efficacy and efficiency, benefiting both the workers and the company (Bernstein et.al.2019). If such interactions are directed to be undertaken by “Corporate Dictators” and are not aligned with Fire Station culture, they are doomed to fail as the participants would feel they are being forced to do something they do not want to do. Forced interactions are not the best way to dispel prejudice (Bernstein et.al. 2019).

I have come up with three strategies that I can implement at work to promote generative intercultural interactions:

1) Partake in the Inclusive Facilities Group as a representative of D crew and share all information with the rest for the crew – this provides an opportunity to share ideas, thoughts, and feelings about gender discourse, gendered social norms and how to be inclusive rather than trying to be neutral or segregating. Because despite the fact that our current workforce want to keep their ablutions facilities separate, the company agenda is not to. Pursuing an organisational goal in a way that makes people feel safe, valued, and dignified can unite us. By being transparent in all communications, and as a conduit for top-down/down-up communications, I can ensure that all members of the team feel valued and know they have a role in decision-making processes (Bernstein et.al.2019). In this space, I will also be engaging with the Corporate working group, thus it is an opportunity for more intercultural interactions on that front as well.

2) Implement a once-a-month afternoon skills session in collaboration with the Station Officer with a different team member per month allocated to design the session. Adaptive contact by regular interactions that build on operational skills provide opportunities to redress stereotypes. Skills sessions are a great way to get people willingly involved in intercultural generative interactions without being overtly a “diversity exercise” (Crisp & Turner, 2011).

3 – Collaborate with the newer SSOs to work up a more modern and relevant gender-inclusive language awareness session. This will have to address the fact that longer-term employees may be apprehensive to engage in a session such as this due to “diversity fatigue”. A new approach needs to be taken that identifies that language use is not about political correctness, and there are no negative consequences for small errors in communication, but rather that it is a framework to make everyone feel comfortable at work, both the majorities who can evolve their communication discourses so they don’t feel anxious and fearful of interactions (Yin & Rancer, 2003), as well as the minorities, who can finally stop being labelled and separated by “Politically Correct” terminology (Hudson, 2018).

Conclusion

Whilst many studies have reported that female firefighters are subject to discrimination, sexism and harassment at work (Perrott, 2016; Sinden et.al. 2013), I must say that I have been fortunate not to have experienced this overtly or intentionally from my male peers. I do feel that gender quotas that prioritize gender over job suitability can certainly lead to invalidation of female firefighters and “tokenism”, but also that the more females there are in the job, the more opportunities there are for generative interactions which will eventually lead to a more diversity inclusive workplace (Bernstein et. al, 20109; Perrott, 2016). However, during this process, if females still experience exclusion they may decide to find alternative employment and thus the disable generative intercultural growth (Bernstein et.al. 2019). This is why it is highly important that there is support for generative intercultural interactions.

REFERENCES

Airservices Australia (2021). How We Work. https://www.airservicesaustralia.com/about-us/how-we-work/

Bernstein, R.S., Bulger,M., Salipante, P., Weisinger, J. (2019). A theory of generative interactions. Journal of Business Ethics, vol. 167, 395-410. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-019-04180-1

Craig, J.M., & Jacobs, R.R. (1985). The effect of working with women on male attitudes towards female firefighters. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 6 (1), 61-74 https://web.a.ebscohost.com/ehost/pdfviewer /pdfviewer?vid=1&sid=1abdc4d0-46f5-42ad-80c9-604ca1703535%4brislin0sdc-v-sessmgr02

Crisp, R.J., & Turner, R.N. (2011). Cognitive adaptation to the experience of social and cultural diversity. Psychological Bulletin, vol. 137, (2), 242-266. https://web.a.ebscohost.com/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?vid=1&sid=f4f55ac5-59a4-4434-80d1-0c94057b76e4%40sessionmgr4006

Eriksen, C. (2019). Negotiating adversity with humour: A case study of wildland firefighter women. Political Geography, vol 68, 139-145. https://doi.org.10.1016/j.polgeo.2018.08.001

Hudson, V.F. (2018). Political Correctness vs Inclusion: What’s the Difference? Retrieved from: Highroad Global Services https://www.highroaders.com/blog/political-correctness-vs-inclusion-whats-the-difference/

Mills, S. (2003). Caught between sexism, anti-sexism and ‘political correctness’: feminist women’s negotiations with naming practices. Discourse & Society, vol. 14 (1). 87-110. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/0957926503014001931

O’Brien, T. (2020). Has inclusion become a barrier to inclusion? Support for Learning, vol 35, (3), 298-311. https://web.b.ebscohost.com/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?vid=1&sid=2b345b18-562e-45fb-9692-e7452039bd3c%40sessionmgr102

Paluk, E.L. (2006). Diversity training and intergroup contact; A call to action research. Journal of Social Issues, vol 62, (3), 577-595. https://web.b.ebscohost.com/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?vid=1&sid=dffb82a1-7dcf-4f33-a59a-52f93ec03e58%40sessionmgr103

Perrott, T. (2016). Beyond ‘Token Firefighters’ Exploring women’s experiences of gender and identity at work. Sociological Research Online, 21, (1), 4, DOI: 10.5153/sro.3832

SBS Australia. (2017). Female Firefighters Fired Up About New Gender Quota.

https://www.sbs.com.au/news/the-feed/female-firefighters-fired-up-about-new-gender-quota

Sinden, K., MacDermid. J., Buckman, S., Davis, B., Matthews, T., & Viola, C. (2013). A qualitative study on the experiences of female firefighters. Work, 45 (1), 97-105. https://web.a.ebscohost.com/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?vid=2&sid=7da401b0-ef04-457a-a252-90d4991b26c1%40sdc-v-sessmgr02

Smith, P.H., & Bamburger, E.T. (2021). Gender inclusivity is not gender neutrality. The Journal of Human Lactation, vol. 37, (3), 441-443

United Nations. (2021). Gender –Inclusive Language. https://www.un.org/en/gender-inclusive-language/guidelines.shtml

Yin, L., & Rancer, A.S. (2003). Sex differences in intercultural communication apprehension, ethnocentrism, and intercultural willingness to communicate. Psychological Reports, vol. 92, 195-200. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.2466/pr0.2003.92.1.195

Final report:

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

An observational study was undertaken at Adelaide Airport Fire Station by a female fighter to assess whether generative intercultural interactions were occurring organically and if not, to identify opportunities to implement strategies to improve communications and engagement to promote generative interactions. Although amongst teams and crews, the observer witnessed many generative interactions both social and task oriented, three opportunities were identified to promote more wide-spread intercultural interactions. The first of these was monthly skills sessions, and the second related to an Inclusive Facilities Project being undertaken by head office. This strategy tried to address the lack of generative intercultural interactions between frontline staff and head office. The third strategy incorporated collaboration with other female firefighters to introduce an open forum learning session for inclusive language to be delivered to all crews. The study concluded that interactions amongst firefighters were generative, whether they were intercultural or not and that participatory strategies that encourage further inclusion and teamwork are enthusiastically welcomed. Undertaking the study also highlighted that in contrast to the generative interactions on the fire station, there are few to zero intercultural interactions across sectors of the organisation. The greatest area of concern was the cultural gap and disparity of desired outcomes for ARFFS, between head office staff and firefighters as this impedes operations, causes unrest, mistrust, and a lack of engagement from frontline staff.

INTRODUCTION

This report is the result of participatory observation undertaken by a female Aviation Rescue Firefighter (myself) to assess whether intercultural interactions on a fire station are generative and promote inclusivity. The research was undertaken to gain a better understanding of fire station culture and to identify opportunities for creating more generative interactions if necessary. Firefighters were observed performing all of their normal daily duties, including social interactions during “down time” on the station. Communication protocols were also noted and three strategies to increase generative cultural interactions were implemented.

BACKGROUND

The Adelaide Airport Fire Station is staffed 24 hours a day, 365 days a year. The fire station is like a home away from home, with crews sharing dining, lounge room, dormitory, office, and amenity facilities over the course of very long shifts. It is not a very diverse work environment, with the only minority represented being the female gender. The Fire Station has 50 employees, and 47 of them are male. Vehicle and equipment inspection and maintenance, training drills, physical training, and incident response are all part of the daily activities at the station. First-aid calls, automated fire alarms, fuel spills, hazardous chemicals, aeroplane events, motor vehicle accidents, and grass fires are all examples of incident response (ASA, 2021). The Aviation Rescue Fire Service (ARFFS) is a semi-disciplined service, with appointed ranks and relevant roles & responsibilities. ARFFS is just one business sector of Airservices Australia, which also manages Air Traffic Control and employs people Australia wide in a range of positions, including engineering, project management, human resources, training, and associated support staff. Different workgroups have their own sub-culture, with ARFFS reporting the highest sense of team engagement and camaraderie (Broderick & Co, 2020).

METHOD

As a participatory observer who is in the same role, facing the same challenges and opportunities as the “participants” of this study, the observer cannot be objective, and the results may therefore be influenced by bias (Bryant, 2015). However, it also means that the observer has a true understanding of the environment and context of the study, lessening the risk of misinterpretation (Guest, et.al.,2013). Being a participatory observer does allow for observations of behaviour in their normal context and opportunities to see what may not be revealed in an interview, or when an “outsider” is present (Guest, et. al., 2013).

STRATEGY

Generative Interactions

1) Creating opportunities for generative interactions promotes intercultural interactions and greater cultural awareness, and also challenges long-held preconceptions (Bernstein et.al. 2019). These interactions need to be inclusive, frequent, collaborative, and promote adaptational behaviours (Bernstein et.al. 2019; Crisp & Turner, 2011). With this in mind, I worked with my Station Officer to create a program for monthly skills sessions to be run by a different team member each time. Regular interactions that showcase team members’ existing skills are a great way to reduce stereotypes and get a better “buy-in” from staff than obvious “diversity training” programs (Crisp & Turner, 2011).

Intercultural Interactions

2) Employers who provide an inclusive work environment are more likely to have staff who are engaged, productive and loyal (Broderick & Co, 2020). Following an independent review of workplace culture at Airservices Australia, twenty recommendations were made. One of these recommendations stated:

“Ensure all Airservices workplaces have appropriate facilities to increase comfort, safety and inclusion for employees, including people of all genders, sexualities, religions, and accessibility needs. Prioritise areas where existing staff do not have appropriate facilities”. (Broderick & Co, 2020)

Despite the fact that Adelaide does already have facilities for all existing staff, the station has been included in Airservices’s “Inclusive Facilities Project”. Although inclusion aims to treat all genders with neutrality, this does not acknowledge that people have been raised in a gendered society and as such have different needs and expectations (Smith & Bamburger, 2021). The expectation of the staff at Adelaide Airport Fire Station is that they have separate facilities for males and females as they do now, and with which they are comfortable. In fact, 40 out of 40 respondents to a company survey did not want the project implemented. If the end user has no need for a project, there is no grounds for trying to create one (Williams, 2017). The negative response to the project was largely based on the lack of consultation and a station-wide strongly held belief that corporate employees have little to no understanding of fire station operations and culture. Project managers who do not understand their end user’s needs will face negative consequences (Williams, 2017). This highlighted another opportunity to implement generative intercultural interactions across working groups. I volunteered to represent D crew in the Inclusive Facilities Group in a bid to close the cultural divide and provide more understanding of workplace culture and operational needs at the station to the corporate employees driving the project. This role provided more opportunities for generative interactions with colleagues on my own crew as well as other crews, but only provided one opportunity to engage with the project manager.

Inclusive Language

Although targeted diversity training can be counter-productive, (Young, 2018), gender inclusive language helps alleviate “tokenism” and exclusion through unwanted attention (Mills, 2003). Whilst some of the management teams are from the “old boys club” days and are reluctant to change, they are also worried about being accused of sexism and try to be politically correct. Unfortunately, this often makes communication awkward and can sometimes make the female staff uncomfortable as it singles them out and highlights their “differences”. Given the historically low percentage of females in firefighting, opportunities for intercultural interactions have been limited and this can cause reluctance from males to engage in communication (Bernstein et.al. 2019; Young & Jones, 2018), especially when men are more reluctant to participate in intercultural interactions in the first place (Yin & Rancer, 2003). After speaking with the other females on station, we each held informal sessions with our crews to introduce to them the concept of using gender inclusive language rather than trying to be “politically correct”, using the United Nations Gender Inclusive Language Guidelines as a reference (Hudson, 2018; United Nations, 2021).

RESULTS

Firefighters work closely together, sharing facilities, in teams and crews doing long shifts and this builds a strong sense of camaraderie. Although not an overtly demographically diverse group, individuals do have a diverse range of interests, beliefs, backgrounds, and life experience. Conversations observed and participated in across a wide range of topics, were always found to be respectful. These interactions are frequent, collaborative, inclusive and are an ongoing contribution to breaking down stereotypes. These interactions are naturally occurring and not an intentional forced program of any kind, which is why they are successful. Past studies have shown that female firefighters have been exposed to harassment, sexism, and discrimination at work (Perrott, 2016; Sinden et. al., 2013) however with more females in the job performing the required tasks and working as part of the team alongside their male counterparts, there is a shifting culture away from such behaviours (Maleta, 2009), and I am happy to report than neither myself nor my female co-workers have experienced any of these issues.

Operational strategies forged to improve cross-sector interactions should focus on imitating this environment for improved outcomes (Bernstein et.al., 2019). Increasing diversity across all functional groups of Airservices would provide greater opportunity for intercultural interactions to occur, and thus become the “norm” (Bernstein et. al., 2019). During such discussions, as part of my observations for this report, I noted that almost all of the employees on station held the view that diversity is good thing, as long it is done correctly. For them, this means ensuring that standards are not lowered for the sake of “diversity hires”. Most reported that even if a Caucasian male was ranked the same as a minority applicant, they understand that it is best for the company and for the future if the minority applicant is hired to help create a more diverse workforce. These are positive results regarding the willingness of firefighters to engage in generative intercultural interactions.

The other thing that emerged was that where there is a problem with intercultural interactions and a lack of generative interactions is between the business management teams and ARFFS. My interim report stated that I thought the consultative forum that was held regarding the Inclusive Facilities Project went well, however since then it has become obvious that Airservices was once again just ticking a box and did not take on board any of the feedback or suggestions from staff. Instead, they have pushed even harder to implement the unwanted changes and have given direction for behavioural changes in the interim. This directive style of leadership is not conducive to long term goals and offering lip service to end users paves the way to project failure (Williams, 2017). Communications with head office should not be one-way only and staff should have a way to communicate directly with executives who are making decisions that will affect them (Baskin, 2021). By spending time at the frontline and observing workers in their own environment, management could gain a more thorough understanding of the requirements of their staff and promote more positive outcomes for projects through improved engagement (Baskin, 2021). The goal of increased intercultural interactions (departmentally) was not realised during this study, and this is due to the fact that corporate employees’ goals do not align with those of frontline workers whose needs and priorities are dismissed (Parand, et. al., 2010).

When discussing the difference between political correctness and inclusive language, I discovered that there had been at least one case of a female at another station taking offence to being called a “guy” in collective morning and/or evening greetings by on-coming staff, i.e.: ‘Hi Guys” and that is why some of the males specifically addressed us females as “Girls” or “Ladies” in a separate address. We assured them that all three of us agree that we do not like or expect that at all and that it actually makes us feel less included, like we are different and need special treatment. This knowledge was gratefully received by the males who were not already aware and most believed that over time that gender-associated terms would be replaced by the UN inclusive language terms that we covered in the learning sessions. Implementing this strategy highlighted the fact that generative intercultural interactions help dispel stereotypes and open communication promotes improved cultural intelligence. (Bernstein et. al., 2019). Furthermore, it showed that inclusion can mean different things to different people, and it is best to ask individuals what they prefer rather than assuming.

DISCUSSION

The findings of this report highlight the consequences of the disparity between management and firefighters on the frontline. Perceptions regarding the necessity and importance of the proposed Inclusive Facilities Project are very oppositional. The resulting conflict and disruption underline the importance of consultation with both working groups and bottom-up approach would be better suited for projects that impact the frontline (Parand et.al., 2010; Young & Jones, 2018). Often the project objectives of upper management have little to no relevance to the priorities of frontline workers and the impact on these staff is not identified (Davis, 1996). A collaborative approach that respects and values the knowledge and input from frontline workers should be undertaken (Baskin, 2020). Currently there are very limited opportunities for firefighters to be involved in decision-making or to provide feedback through intercultural interactions (Broderick & Co.,2020). This would also promote opportunities for generative intercultural interactions across business groups. Participatory strategies garner greater engagement from employees (Davis, 1996) and an inclusive and just culture that values all employees empowers people to contribute and to challenge authority without fear of retribution (Broderick & Co., 2020).

The Broderick review noted that ARFFS has the most unity of all the business groups and whilst there was widespread reporting across all sectors of bullying and harassment from direct and upper management, complaints of a control and command directorial approach to management, problems with communication protocols, lack of engagement, and a fear of speaking up, there were no reported complaints about Fire Station facilities yet this is where the company has proceeded to focus its efforts on addressing the review. Where there is a conflict between organisational goals, these need to be addressed (Davis, 1996). To get the firefighters on board with the project, the project management team need to understand the firefighter’s role and daily operational requirements and show how the project will benefit them and help their meet their own operational goals. If there are none, then changes need to be made to the project proposal (Davis, 1996). Consultation also needs to occur specifically with any employees who are not comfortable with facilities, or behaviours and may have needs that are not being addresses. This can come across as the person being a “problem” so they may be reluctant to speak up. A positive safety culture promotes engagement from all employees, values their contributions, encourages people to speak up and provides avenues for them to do so (Broderick & Co., 2020). Employees need to feel that they can raise issues without judgment and retribution, and this benefits the company through positive culture changes, employee engagement and loyalty (Broderick & Co., 2020)

CONCLUSION

After the success of implementing the strategies identified and how well received the initiatives were by my team, I can report that the intercultural interactions at a station level, are definitely generative. These interactions are frequent, inclusive, and collaborative and through respectful communication they help dispel stereotypes. Although we generally only have the opportunity to interact with our own crew, recently there have been other social events to which everyone was invited, and these provided more opportunities for generative interactions. Whilst intercultural interactions amongst firefighters were observed to be positive and generative, including across ranks, that cannot be said of interactions between business groups at Airservices Australia.

It is disappointing that of the 20 recommendations from the Broderick review, the one that is being addressed by management is one that doesn’t affect them and is not wanted by the people it will affect.

The fact that the project is getting pushed ahead disregarding feedback from the end users shows clearly that the recommendations regarding shows that management do not value the input of their staff. There is a vast cultural divide between corporate and frontline workers (in this case, firefighters), and although a station visit from a project manager did occur, this has proven not to promote generative interactions, nor did the results and feedback get handled in a respectful and inclusive manner. Rather, the feedback was dismissed and further strategies to force change were implemented. The disparities between what firefighters identify as critical needs and where “corporate” are willing to spend time and money has united the crews more than ever, despite the disruption and heated debates it has caused. It has highlighted the culture gap between “us” and “them” once again.

REFERENCES

Airservices Australia [ASA] (2021). How We Work. https://www.airservicesaustralia.com/about-us/how-we-work/

Baskin, E. (2021) The Frontline Knows What Corporate Doesn’t. https://www.tribeinc.com/2021/09/09/the-frontline-knows-what-corporate-doesnt/

Baskin E.(2021). Bridging the Horizontal Divide Between Leadership and Your Frontline. https://atlanta.iabc.com/bridging-the-horizontal-divide-between-leadership-and-your-frontline/

Bernstein, R.S., Bulger,M., Salipante, P., Weisinger, J. (2019). A theory of generative interactions. Journal of Business Ethics, vol. 167, 395-410. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-019-04180-1

Crisp, R.J., & Turner, R.N. (2011). Cognitive adaptation to the experience of social and cultural diversity. Psychological Bulletin, vol. 137, (2), 242-266. https://web.a.ebscohost.com/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?vid=1&sid=f4f55ac5-59a4-4434-80d1-0c94057b76e4%40sessionmgr4006

Davis, T.R.R. (1996). Developing an employee balanced scorecard: linking frontline performance to corporate objectives. https://go.gale.com/ps/i.do?p=ITOF&u=ntu&id =GALE%7CA18515644&v =2.1&it=r

Guest, G., Namey, E.E., & Mitchell, M.L. (2013). Collecting qualitative data: A field manual for applied research. SAGE Publications. DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4135/9781506374680.n3

Elizabeth Broderick & Co. (2020). A Review of Culture at Airservices Australia. https://www.airservicesaustralia.com/wp-content/uploads/Air-Services-Culture-Review.pdf

Hudson, V.F. (2018). Political Correctness vs Inclusion: What’s the Difference? Retrieved from: Highroad Global Services https://www.highroaders.com/blog/political-correctness-vs-inclusion-whats-the-difference/

Maleta, Y.(2009). Playing with Fire, Gender at work and the Australian female cultural experience within rural firefighting. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/1440783309335647

Mills, S. (2003). Caught between sexism, anti-sexism and ‘political correctness’: feminist women’s negotiations with naming practices. Discourse & Society, vol. 14 (1). 87-110. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/0957926503014001931

Parand, A., Burnett, S., Benn, J., Ponto, A., Iskander, S., & Vincent, C. (2010). The Disparity of Frontline Clinical Staff and Manager’s perceptions of a quality and patient safety initiative. https ://web .a.ebscohost.com/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?vid=1&sid=0a54ba40-b6b1-432d-a004-5d0c9b6d0201%40sdc-v-sessmgr03

Perrott, T. (2016). Beyond ‘Token Firefighters’ Exploring women’s experiences of gender and identity at work. Sociological Research Online, 21, (1), 4, DOI: 10.5153/sro.3832

Sinden, K., MacDermid. J., Buckman, S., Davis, B., Matthews, T., & Viola, C. (2013). A qualitative study on the experiences of female firefighters. Work, 45 (1), 97-105. https://web.a.ebscohost.com/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?vid=2&sid=7da401b0-ef04-457a-a252-90d4991b26c1%40sdc-v-sessmgr02

Smith, P.H., & Bamburger, E.T. (2021). Gender inclusivity is not gender neutrality. The Journal of Human Lactation, vol. 37, (3), 441-443

United Nations. (2021). Gender –Inclusive Language. https://www.un.org/en/gender-inclusive-language/guidelines.shtml

Yin, L., & Rancer, A.S. (2003). Sex differences in intercultural communication apprehension, ethnocentrism, and intercultural willingness to communicate. Psychological Reports, vol. 92, 195-200. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.2466/pr0.2003.92.1.19

Media Attributions

- Airservices Australia 2021

- Indy100 2017

- QueerGuru 2017

- Dreamseat 2021

- Pinterest 2021

- arrf1

- arrf2