6 Indigenous Business Perspectives

Terry Wickey has generously shared his work and story with us to provide a strong Indigenous perspective on inter-cultural intelligence and capability, lifelong learning, business and success.

In our teleconferences regarding his learning and knowledge over the years, Terry shared many deep insights and experiences of being a multi-dimensional cultural being in society. Speaking through the voice of Mother Earth sustainability from instinctive listening, seeing, feeling, touch and taste, Terry’s cultural belonging is connected to identity, empowerment, healing, respect and the spirit. Coming from living in a darkness and making ends meet, to a world that has colonial structures that disembody Aboriginal spirits, he is making meaning between two paradigms. Terry is exploring different patterns of human beliefs, as he turns to Mother Earth belonging when there is a paradox.

Terry’s professional experiences of Rugby League was an Indigenous family legacy. In another paradox, Terry also experienced the different rites of passage, impacting health and self-worth, which led to confusion and entering the criminal system as a younger Indigenous man. There was an understanding that it was a privilege as a rite of passage to go to jail to be accepted as a man. These experiences grew an advanced awareness of how gender, culture, and race shaped his understanding of himself and others. One of many powerful comments Terry made was how sports can normalise male violence and disconnection from cultural governance. His heightened awareness created pathways for Terry to develop his organisation, website, and career goals, making opportunities for young people’s lifelong learning and space to be safe, under his ancestral guidance.

Terry described spending every morning on Country developing increased self -awareness, getting back to culture, and feeling his way into his days. Staying true to his Lore and the cultural laws he is connected to helps him continue to work in sustainable ways, to develop more Indigenous executive presence in commerce, sports and civic life.

Terry shares three of his papers here, and a presentation he prepared on communicating career objectives in his long career in Business and Sports Development.

- Indigenous Business Sustainability

- The Set Up: Black-cladding

- Gender Disparity in the Workplace

Click this link to read Terry’s Presentation: WickeyT_

Paper1: Indigenous Business Sustainability

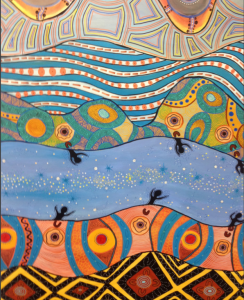

By Cecily Wellington-Carpenter (Mother Earth Sustainability) Cecily Carpenter, now past, gave me permission to use this image to share the story telling of Rainbow Serpent Dreaming sustainability.

Introduction

Business sustainability is the management of resources for society to satisfy consumer needs now and into the future. It is also about the elimination of waste and wise recycling, by developing environmentally friendly production processes. The issue to discuss is how Indigenous values driven management practices provide an alternative management approach for all business. This is a management philosophy and practice, based on Mother Earth sustainability. It is founded in culturally collective values and practices, for this generation and for the generations beyond. I will also discuss how management theories are actually underpinned by Indigenous frameworks that have led to extrinsic and intrinsic motivations for employees. I will use this opportunity to investigate my own business website to see where the three sustainability pillars are visible, and what needs to be included in the future. Mother Earth sustainability is a long-term solution for all business managers in Australia to motivate their staff, focus on staff wellbeing and be sustainable for a global future.

Background

Globally, The United Nations has led the sustainability agenda. In 1972, the United Nations Conference on Human Development declared, ‘Man has a special responsibility to safeguard and wisely manage the heritage of wildlife and its habitat, which are now gravely imperiled by a combination of adverse factors. Nature conservation, including wildlife, must therefore receive importance in planning for economic development (Kumari 2007)’. It was the United Nations report of 1987, ‘Our Common Future’, that combined the issues of environmental and economic development into one global issue (Schermerhorn 2016 p.153). Further to the 1987 report, the 2nd Earth Summit in Rio de Janero in 1992 introduced new values to the sustainability debate. There are now three pillars of sustainability that include environment, social and economic accountability. These new priorities combined, equal the Triple Bottom Line Approach (Schermerhorn 2016 p.153). The environment and sustainable development are inextricably linked. 2 Fifteen years later, the Brundtland Commission’s report Our Common Future defined sustainable development for the first time, as: “Satisfying the needs of the present generation without compromising the chance future generations to satisfy theirs.” I will apply these global priorities to the Australian Indigenous business website, my business website, Rainbow Serpent Dreaming (Wickey 2021), taking this essay from a global to local sustainability management discussion, using Mother Earth sustainability.

Indigenous Recognition and Sustainable Management

The United Nations sustainability agenda is important, because as Indigenous people, we often have to go outside our own country for recognition of our rights. Schlange (2009), for example, investigated how critical to success managing the engagement of stakeholders was for sustainability entrepreneurs to realise their business goals. There is an opportunity to lead business into the future by reframing sustainable management practices that value collective well-being over economic output. Building on these changing values is The United Nations General Assembly adopted 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. This is the global Indigenous sustainability marker of accountability for the next 15 years.

Sustainability issue for managers and employees

As an Indigenous man and business owner and manager, I am promoting that sustainable management values and Indigenous values are aligned with Mother Earth and the social culture of sharing and caring and belonging connection, to each other and all living entities. This is essential to my business management practice and Indigenous sustainability because it is about survival and competition of natural selection. To be a sustainable business and have sustainable management, there needs to be an integrated system of interdependence of management care and strategy to address the three pillars for long term business management sustainability practices to address these pillars for this generation and the next generations.

Motivational Management Approaches

Motivation theories are applied in business practices to motivate employees. The aim is to use these theories to improve sustainability. The roots of sustainable practices, lie not only in the traditional Western way of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation, but are founded in Mother Earth thinking; being and doing of Indigenous ways. Interestingly, Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs is based on an interpretation of the Indigenous ways of the Blackfoot People from Canada (Michel 2014; Feigenbaum & Smith 2019). Maslow’s interpretive hierarchy from this experience with the Blackfoot people, has become a foundation in the history of Western management.

This theory is an approach that is categorised into lower and higher order needs with every step linked to higher esteem and good feeling. Where this does not work with sustainability is Maslow’s Deficit Principle. This states that satisfaction is not a motivating behaviour, not a sustainable behaviour in business. Maslow, in a 1955 symposium, discussed deficiency motivation and growth motivation (Maslow 1955), quite different from the steps below in Maslow’s Progression Principle that identifies that a need at one level does not activate until the lower-level need is satisfied (Schermerhorn 2016 p. 414), like a step ladder. With blood-lore and sharing and caring in Mother Earth thinking, there is a sustainable instinctive natural process that is interconnected, without steps.

In Indigenous lore, lower and higher-level needs were and are interconnected, there is no step-by-step process. In my experience at work, this could be one reason why Indigenous employees find it challenging to work in Western management workplaces that have a hierarchy of rewards. The higher needs interact with lower-level needs for a sustainable management practices to consider who their employees are and build a relationship to identify their motivators, whether they be intrinsic or extrinsic, and design management motivational strategies that respond to their connection to the workplace and their desires to invoke sustainability thinking. This could be achieved through intrinsic motivators of a business promoting sustainability values. Management approaches to sustainability of the three pillars are rooted in intrinsic and extrinsic rewards. Intrinsic rewards happen naturally. They are embedded in their work such as performing a good job, connecting with the values and spirit of that person. This is embedded in Self Determination Theory, a theory based on the psychological needs of competence, autonomy, and relatedness focused on motivation and well-being (Ryan & Deci 2017).

Extrinsic motivators are valued outcomes rewarded to an employee by another person. Examples could be paid bonuses, time in lieu, promotions, verbal praise and acknowledge production outcomes (Schermerhorn 2016 p. 411). In my business, this is often in the positive feedback they get from clients and other employees. This can occur in person, in team meeting and through social media. Innovation through ‘The adoption of social media appears to have engendered new paradigms of public engagement (Lovejoy and Saxton 2012 p. 1)’. Websites, Twitter, Facebook and Instagram are the new carriers of information and instant motivators for employees and information to stakeholders. It is said that ‘almost every non‐profit was founded explicitly to respond to a community need’. In line with Indigenous values of the collective good, philanthropy promotes intrinsic and extrinsic motivation in management practice for sustainability. In sport, the role of athletes has taken a green turn by leveraging the role of athletes in organisations to communicate sustainability and the environment. It became an enabler of sustainable development in the UN 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development A/RES/70/1 paragraph 37. This leads to a flow between sustainability, sport, and innovation.

Innovation is the key to generational sustainability. ‘…technological and innovations offer a hope for individuals and organisations who wish to reap the potential benefits from a sustainable approach to doing business (Schermerhorn 2016 p. 152)’. To take the discussion further, I would say Mother Earth thinking is the key to generational sustainability through renewal and regeneration. I will combine Mother Earth thinking and the environmental, social and economic sustainable markers of the triple bottom line approach (Schermerhorn 2016 p.153) to look at how I address sustainability on my business website.

Rainbow Serpent Dreaming

On the website of my non-profit organisation, Rainbow Serpent Dreaming’s landing page is clear about the Indigenous values connecting culture to sustainability through sport. It is a service. I will address the website against the three pillars of sustainable development. The purpose is to mentor and support at risk youth into the professionalism in competitive sport. By addressing issues as a non-profit organisation, Rainbow Serpent Dreaming, adds value to the community by addressing issues that harm our community impacting young people’s futures. This aligns with the Shared Value practice of management that creates value for society (Shermerhorn 2016 p. 163). In my business, it is achieved through the motivation of employees, who are professional sporting identities in their own right and elders that have relevant experiences to share and guide the way.

“Rainbow Serpent Dreaming Indigenous Corporation is about IDENTITY, EMPOWERMENT, HEALING and RESPECT it’s to create opportunities for indigenous kids to better adapt to the professionalism of sport to challenge cultural diversity and be competitive at professional level (Wickey 2021)”.

Identity, empowerment, healing and respect underpin the fight for survival, in a colonised nation. The current trend is for value driven business to be sustainable and to create value for customers. The shared values of local responsibility and sustainable responsibility appeal to all stakeholders.

Environment

Environmental sustainability is not explicit on the website. It is embedded in the universal understanding of the connection and belonging of Mother Earth. As the business is a service, there is a minimal carbon footprint. The environment that is created is a culturally and institutionally safe one for employees and clients. This is one area that I have identified needs to clearer on the website. ‘The contribution of sport to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) is limited by the current skills and knowledge gap (Joie Leigh 2020 p. 1)’. This business provides a sustainable environment to develop these skills and knowledge under the expert mentoring of professional sporting initiators.

Social

Under the ‘What We Do’ section the website clearly states the purpose of the organisation and its impactful contribution to social sustainability. The stakeholders are both Indigenous and non-Indigenous funding bodies, philanthropists and sporting identities as employees working collaboratively to improve the economic, social and environmental outcome for Indigenous youth to pursue a sustainable career in their chosen sport. This is achieved when youth are mentored to navigate the life challenges, with a strong cultural connection to country, healing, respect for self and others.

A group of both Indigenous and non-Indigenous sporting professionals have come together to satisfy a need for the assistance of Indigenous youth. We noticed that there is a lack of resources available to Indigenous youth wishing to pursue a sporting career. Support such as fitness and exercise, diet and welfare and career counselling are not typically available without large cost. The foundation came together to provide these services (Wickey 2021).

Organisations like mine are realising that embracing sustainable changes and Mother Earth thinking are about shared values and respectful practices. There are ways for organisations and managers to motivate their employees to practice sustainability and be sustainable into the future. It is about connecting sustainable practices with heartful practices of intrinsic rewards that benefit the business, as the business benefits the whole community and extrinsic rewards that are outwardly motivating. This is shown in the next example.

The foundation is working in the areas of youth diversion, drug/alcohol substance abuse and cultural identity healing. A strong network of sports professional’s past and present will be role models to provide advice and stories about their experiences, how they became professional athletes and what inspired them to achieve their goals and keep them on the right track to better adapt the cultural diversity of IDENTITY to succeed both on and off the field (Wickey 2021).

Economic

Economic sustainability for this non-profit organisation is focused on empowering the sporting youth clients to understand and have some control over the direction of their economic sustainability. This is about developing literacy and accountability around legal contracts with clear understanding of their obligations. This is not explicit on the website and will be added in the future. As a non-profit economic sustainability is an ongoing challenge. ‘A significant determinant of an NPO’s success is its financial sustainability and its leadership’s ability to adapt to changing financial climates ( Brown 2019; Schatteman & Waymire 2017).’ This is the pillar of sustainability in the organisation that is needs strengthening and visibility on the website to achieve a true triple bottom line approach (Schermerhorn 2016 p.153). Incorporating the business economic sustainability into the strategic plan will enable the organisation to further innovate and move forward on achieving business sustainability for all the stakeholders.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this sustainability management task has given me the opportunity to learn more about management motivators and the theories behind them. I have focused on Maslow’s contribution as there is the strong Indigenous influence that has not been acknowledged in Western management practices. The United Nations has many declarations to address sustainability to save Mother Earth and we all need to be learning about Mother Earth thinking and applying it in our daily business practice for wellbeing and our survival. The Rainbow Serpent Dreaming website, my business example, will benefit from making sustainable practices and management theory clear to all stakeholders, to attract philanthropic and commercial opportunities for sustainable economic stability for the business to pay its way forward.

References

Australian Competition and Consumer Commission 2015, Report on the Australian petroleum market: June quarter 2015, Australian Government, http://www.accc.gov.au/system/files/1004_ACCC%20Petrol%20Report_Macro_Jul y%202015_FA.pdf

Brown, L.T., 2019, Sustainability Strategies for Nonprofit Organizations During General Economic Downturns.

Feigenbaum, K.D. and Smith, R.A., 2019, Historical narratives: Abraham Maslow and Blackfoot interpretations. The Humanistic Psychologis

Krishna Kumari, A 2007, Evolution of Environmental Legislation. Evolution of Environmental Legislation (January 2007).

Leigh J Jan 20th 2020, Bridging Gap Environmental Sustainability Report. https://www.sportanddev.org/en/article/news/bridging-gap-environmental-sustainability-through-sport

Lovejoy, K. and Saxton, G.D., 2012, Information, community, and action: How nonprofit organizations use social media. Journal of computer-mediated communication, 17(3), pp.337-353

Maslow, A 1955, Deficiency motivation and growth motivation. In Nebraska symposium on motivation (Vol. 3, pp. 1-30).

Michel, K 2014, Maslow’s hierarchy connected to Blackfoot belief

Ryan, R and Deci, E.L 2017, Self-determination theory: Basic psychological needs in motivation, development, and wellness. Guilford Publications.

Rainbowserpentdreaming, Instagram update, 16 May 2021, https://www.instagram.com/serpentselitesportsprograms

Schatteman, A & Waymire, T 2017, The state of nonprofit finance research across disciplines. Nonprofit Management and Leadership,28(1):25–137. doi:10.1002/nml.21269

Schermerhorn, John R 2016, Management, 6th Asia-Pacific Edition, Wiley, Melbourne

Schlange, L 2009, Stakeholder identification in sustainability entrepreneurship. Greener Management International, (55).

UNITED NATIONS OFFICE ON SPORT FOR DEVELOPMENT AND PEACE, Sport and the Sustainable Development Goals, An overview outlining the contribution of sport to the SDGs, United Nations https://www.un.org/sport/sites/www.un.org.sport/files/ckfiles/files/Sport_for_SDGs_finalversion9.pdf

United Nations 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development 2015, Transforming Our World: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, Department of Economic and Social Affairs Indigenous Peoples https://www.un.org/development/desa/indigenouspeoples/focus-areas/post-2015-agenda/the-sustainable-development-goals-sdgs-and-indigenous.html

Wickey T. 2021. Rainbow Serpent Dreaming, https://www.rainbowserpentdreaming.org.au/.

Paper2: The Set Up: Black-cladding

Introduction

The ‘July 1st, 2015, generated 2.7 billion in contracts for the Indigenous business sector in Australia, a breakdown of 9,527 contracts being awarded to 1,935 Indigenous businesses by the Commonwealth and our major suppliers (National Indigenous Australian’s Agency 2020).’ This paper analyses the current economic phenomena of black-cladding against The Set Up: racist business culture corrosive to Aboriginal business and values, through Australian government Indigenous Procurement Processes (IPP). The analysis will refer to Foley’s (2004) thesis, to ground the analysis in an ethics and cultural values framework. Black-cladding is addressed in the framework of ethics and values, structural racism through government procurement and mitigating risk through due diligence.

The Ethics and Values

It is reported that accounting literature has a focus on accounting ‘for’ Indigenous peoples not accounting ‘by’ Indigenous peoples (Buhr 2011, p. 139 as cited in Lombardi, 2016). Burh (2011) flipped the ethics paradigm by investigating what accounting might look like ‘by’ Indigenous peoples. It was important to acknowledge the historical devastation of accounting leading to genocide. The literature points towards a new way of thinking and doing accounting that recognises that accounting can be an empowerment tool. According to Foley (2004), non-Indigenous people need to understand and be empathic to Indigenous cultural values. Chrobot-Mason, Campbell and Vason (2020), however, are uncompromising in their article, ‘Whiteness in Organizations: From White Supremacy to Allyship’. On their comment of Australia’s business values, white superiority and dominance cast a negative view of Australia’s indigenous people and pressure them into fitting the mold of Western culture, beliefs, and values. This is reinforced through the argument of Moreton-Robinson (2015), that aboriginal people interact through their own codes of communication, through what is termed ‘kinship’ in Australia, but this is uncommon in organisational culture which requires different, more white norms, with different terms of engagement (p.224).

The concept of Indigenous cultural values is an important topic for non-Indigenous people to come to terms with, be sensitive to, show empathy for. That will enable them to work constructively within Indigenous business networks. Aboriginal culture must be maintained. A critical issue of identity and integrity is that Indigenous entrepreneurs can both be successful in mainstream business and uphold their Aboriginality. Or in other words, they do not necessarily have to become culturally Anglo-European (non-indigenous) or ‘White’ to succeed. To maintain aboriginal identity in the business sector, the Indigenous entrepreneur must maintain their cultural beliefs and respect across cultures with accountability and a strong voice. It was generally agreed that cultural beliefs and respect was a community and/or personal undertaking, which is not measurable by external Anglo-European definitions (Foley 2004, p. 231). This needs to change. “Strong views remain concerning protocol and ethics, what has evolved are contemporary Indigenous values that allow the Indigenous Australian to maintain cultural standards revolving around kinship in contemporary Australia (Foley 2014, p. 13)”. “My uncles fought for land rights and made noise. That’s why I am here today. Being culturally cognisant of Indigenous history and human rights in contemporary Australia demands recognition and a place in the policy making mechanism of the Nation (Wickey 2020)”.

Government Procurement

Australia’s Commonwealth Indigenous Procurement Policy (IPP) was launched in July 2015 (National Indigenous Australian’s Agency, 2020). It was created to elevate opportunities for Indigenous businesses. By being aware of this policy, and embracing its intent, businesses have the opportunity to build relationships with Indigenous suppliers and contractors — to both differentiate themselves from competitors and to support Indigenous business social and economic development. It began a trend to make government procurement changes in how goods and services were sourced from Indigenous businesses. Indigenous business now has procurement options ahead of open tender. Although this may be viewed in a positive way, it leaves Indigenous business operators open to the risk of black-cladding. It encourages non-Indigenous led businesses to build relationships with Indigenous suppliers and contractors only to the point of 51% Indigenous owned and operated. There is the potential to use what was intended as an Indigenous business empowerment platform, as an opportunist process by manipulating Indigenous business owners to ‘be the front man’, where in fact the business applying for tender could be non-Indigenous driven. This leads to black-cladding and structural racism.

Black-cladding and structural racism

“Black cladding is the unethical practice of non-Indigenous businesses passing themselves off as Indigenous businesses in order to benefit from Indigenous policies and programs (Burrell 2015, p. 1)”. Black-cladding is paternalistic structural racism. Foley (2004) acknowledges that the main blockade to business growth and success within Australia, is racism (p. 270).” Since early 2016, black-cladding has been pursued initially through investigative journalism. The Indigenous Affairs Minister at the time exposed business opportunists who were taking advantage of the government procurement system. As a result of the corruption, a business council was established (Easton 2018). The new business council’s role was to prevent wrongdoing and improve procurement processes for government contracts, for businesses that met the criteria of Indigenous ownership and employment. One of the strategies to support the newly formed business council was to use the Indigenous organisation Supply. Supply Nation has established a 1600 strong Indigenous business directory. There is now a rigorous process of registration and accreditation (Supply Nation 2020). July 1st, 2015 generated 2.7 billion for the Indigenous business sector resulting in identification of black-cladding as a risk and he convinced the Minister for Indigenous Affairs to address joint ventures that have taken advantage of the Federal Government’s Indigenous Procurement Policy (IPP) (Easton 2018). This then raises the issue of mitigating risk of black-cladding through due diligence.

Mitigating risk

Mitigating risk of black-cladding can be achieved through due diligence. The issue of joint-venture risk through black-cladding, through business contractors working with Indigenous businesses have taken advantage of the 3% Indigenous procurement initiative (Jenke and Sentina 2018). The 3% Indigenous procurement initiative is now embedded in the 2015 IPP as a strategy to mitigate risk. Joint-ventures are also now required to register through Supply Nation. There are, however, potential issues of a different kind of gatekeeping: Indigenous supplier preferences through Supply Nation. Mitigating risk is a complex process but needs to be embedded in policy as an ongoing priority to ensure Indigenous businesses are accessible to the wider Australian and International market, whilst ensuring cultural integrity through strong accountability.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this paper analysed the current economic phenomena of black-cladding targeting Indigenous business in Australia. This practice undermines the ethics and cultural values that is the foundation and point of difference in Indigenous business practice. Australia’s Commonwealth Indigenous Procurement Policy (2015) was implemented with the purpose of identifying Indigenous businesses to create more opportunity for access to tender and contracts. This policy backfired when it was declared that only 51% of a business needed to be Indigenous owned to qualify. Even with mitigating risk strategies, this leaves Indigenous businesses, and particularly emerging Indigenous businesses, at risk of black-cladding and ongoing structurally paternalistic racist practices calling into question the validity of the whole Australia’s Commonwealth Indigenous Procurement Policy.

References:

Buhr, N., 2011. Indigenous peoples in the accounting literature: Time for a plot change and some Canadian suggestions. Accounting History, 16(2), pp.139-160.

Burrell, A. 2015. ‘Beware ‘black cladding’ as indigenous vie for business’ The Australian <http://www.theaustralian.com.au/national-affairs/indigenous/beware-black-cladding-as-indigenous-vie-for-business/news-story/f7ebea079f6ca57fc00a20c021c0ac3c>.

Chrobot-Mason, D., Campbell, K. and Vason, T., 2020. Whiteness in Organizations: From White Supremacy to Allyship. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Business and Management.

Easton, S. Oct 5th 2018. Indigenous Procurement Policy: Minister Finally Cracks Down on Black Cladding. The Mandarin https://www.themandarin.com.au/99579-delayed-action-minister-cracks-down-on-companies-gaming-the-indigenous-procurement-policy/

Foley, D., 2004. Understanding Indigenous entrepreneurship: A case study analysis (Doctoral dissertation, University of Queensland).

Jenke, T & M. Sentina 2018. IBA Indigenous Joint Ventures Information Guide, Terri Janke and Company, https://www.iba.gov.au/wpcontent/uploads/Indigenous_JV_InfoGuide.pdf

Lombardi, L., 2016. Disempowerment and empowerment of accounting: an Indigenous accounting context. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal.

National Indigenous Australian’s Agency, 2020. Indigenous Procurement Policy, https://www.niaa.gov.au/indigenous-affairs/economic-development/indigenous-procurement-policy-ipp

Supply Nation, 2020. How we verify Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander businesses https://supplynation.org.au/benefits/indigenous-business/

Wickey, T., 2020. Personal Statement

Gender Disparity in the Workplace

Addressing a Scenario

“Leaders and managers need to convey their point of view to employees and employees must persuade leaders and employers to appreciate their point of view” (Dwyer 2019, p. 135).

Introduction

In this business communication essay, I will look at how to raise the issue of gender disparities in the workplace and how to address them as a new employee. In this scenario, I am an employee wanting to communicate the gender disparity of what I see, to both colleagues and management. The top-level management positions are mainly occupied by men. It has also been made clear that most female employees earn less than their male counterparts. As a relatively new employee I am wary of losing my job, but I want to speak up about the gender disparity at my workplace. This is a medium sized company in Sydney, impacted financially by the Corona Virus pandemic. There are many considerations. The main issue is related to values and where I am in Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, and if I believe I need to compromise my values and stay silent, to keep paying the rent. This is a communication issue but also an internal issue, an integrity issue.

Critically analysing the situation, I will look at business communication theories to convey my concerns. I will identify tools and strategies that I could use to present my point of view to my colleagues and top management. The thesis statement is that ineffective channels of communication create unsafe working environments where the employees are unclear about rights and roles and therefore don’t perform as well as they could. This leads to negativity and anxiety in the workplace environment, where gender disparity is the obvious issue, in this case, or is it the uncertainty of being able to communicate ideas and opinions constructively to management without fear of retribution? Which communication channels will work the best for my needs and values?

Analysis of business communication theories

I can apply Schein’s Theory (Dwyer 2019, p. 132). Schein’s theory will help me to think about and reflect on the organisational culture and values of what the organisation represents and how the behaviour in the business is reflected in its culture. By critically analysing Schein’s Theory, in this scenario, there appears to be basic underlying assumptions that have created a male dominated culture in this Sydney based real estate company. For me as a relatively new employee, I must think about my own needs and as the job has just started and where do you draw the line? Do you wait until your probation is up before you speak your concerns or ask another person who has been there for a long time about it?

Milliken, Morrison and Hewlin (2003) did a study on employee silence and why employees don’t speak up. It was found that employees didn’t feel comfortable talking about equity issues with their employers for fear of being labelled a problem or losing their job. Schein identified that this could be embedded at a deep level of organisational culture, so I would observe how people around me, top management and colleagues, respond to any unconscious perceptions or opinions at the agency (Dwyer 2019, p.132). Schein’s theory is like the unconscious bias culture in many non-diverse or mono-cultural workplaces, that I am aware of, as an Aboriginal man (Newbery 2019). Sui (2021) acknowledges that women are usually at the heart of diversity studies but there is a wider diversity issue. This is the issue of where unconscious bias is embedded into business culture and that the business is probably missing out on the strengths of diverse groups. In this scenario, it is the leadership and representation of women in management. This leads to tools and strategies to communicate my concerns to colleagues and management.

Tools and strategies

There are tools and strategies that can help me present my point of view to my colleagues as well as the top management. There is no indication in the scenario but whether the company has a centralised or decentralised structure, will influence my tools and strategies to communicate my concerns (Dwyer 2019, p.139). As this is a medium-sized real-estate company, a simple structure is likely.

This is basically an environment where employees communicate directly with the managers and there is more transparency than a management system that is a hierarchy, where employees have to go through different levels to communicate. Being a more autonomous workplace, employees are more accountable due to the decentralised structure. With men predominantly at the top of the management structure, I am thinking there is a combination of both hierarchical as in patriarchal management culture and decentralised structure as real-estate agents need to have a lot of autonomy with a high level of accountability due to the sales environment. I would talk to people face to face and raise the issues in email and in meetings. I would justify communicating my concerns by showing that there could some benefits to including women on the management team.

Conclusion

The main points of the essay are to demonstrate the validity of the thesis statement, ‘that ineffective channels of communication create unsafe working environments where the employees are unclear about rights and roles.’ Using Schein’s theory, I realised that there was unconscious bias in the workplace around the lack of diversity where women were left out of the management. By using the tools and strategies of talking to colleagues, raising issues in emails and through meetings, I was about to show how including women might benefit the company. I did do all of this after my probation period was up because I really needed my job in times of Covid. I can apply my learning from this assessment in my own workplace, where I have recently been given more responsibility in a management role. Even in times of crisis, it is essential that there are clear channels of communication to ensure that employees are feeling safe and performing their best and that management is receptive to employee suggestions.

References

Dwyer, J 2019, Communication for Business and the Professions: Strategies and Skills, Pearson Education Australia, 2019. ProQuest Ebook Central, http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/cdu/detail.action?docID=5967534.

Milliken, F Morrison J & Hewlin, P 2003, ‘An exploratory study of employee silence: Issues that employees don’t communicate upward and why’. Journal of management studies, 40(6):1453-1476 pp.1453-1476.

Newbery, C August 8th, 2019, ‘What is unconscious bias in the workplace, and how can we tackle it?’ CIPHR https://www.ciphr.com/features/unconscious-bias-in-the-workplace/

Siu, B 2021, ‘4 Perceptions and Attitudes’, In Opening Doors to Diversity in Leadership (66-108). University of Toronto Press.

Media Attributions

- Wickey thumbnail

- mother earth